Soft feet

A (North) American baby in pain and paradise

I like to travel, but I’m not a very good tourist. This is partly how two weeks ago I came to be sitting in the Pacific surf with my feet full of sea urchin spines, exploring the sonic spectrum between laughter, hyperventilation and howling, watching my peripheral vision depopulate as the few other beachgoers at this end of the resort realized that whatever the hell this was, it wasn’t ending anytime soon, and decamped to find the relaxation they’d been promised.

I like relaxing, too, supposedly. But luxury starts to make me itch after about 30 minutes; I avoid it as a rule. When I won a work award entitling me to a luxury vacation in a country I love with a couple dozen coworkers and their plus-ones, oh wow! and oh no sang out in harmony within me. It was going to be wonderful. And it was going to be work, trying to emit the right chill and sociable vibe amid colleagues and the army it takes to run a five-star resort in Central America for those with the hubris to call themselves just plain Americans, as if they were the only ones. (Which more than one local was eager to remind me on my last, non-luxury trip to the country: Usted es NORTEamericana. Nobody pointed that out to me this time.)

I wiped some of the rust off my spoken Spanish before arriving, even knowing I likely wouldn’t need to use it at all and for that reason would probably feel awkward about trotting it out. Look at me, the teacher’s pet of Latin America. Being a tourist—being revealed as a tourist—is such an embarrassing condition. I wish I didn’t feel this way, but it activates the same flight response in me as any performance that demands audience participation. Sure, yes, much of this may be designed for my benefit, but couldn’t we pretend that you can’t see me, here among the other amateurs clapping off beat and singing off key?

Plus, I learned, at a place like this, a hospitality job is not what you do while you’re trying to figure out or fight your way toward what you really want to do. It’s probably what you spent four years explicitly training for in college, then many more working your way up the resort ladder, star by star. The nearest city had become a center of this kind of education in recent years, our guide said.

This knowledge was additionally embarrassing. In other surroundings I could at least have in common with my army of helpers the experience of fumbling through a service industry job. But no—these were as highly trained as zookeepers in the needs of their charges. And I didn’t want to insult their expertise. But getting my bags carried, being ushered into a golf cart to travel the distance of a city block or two—why, when I myself had two working arms and feet?

Then suddenly I did not have two working feet, and how I wanted that army to rush to my side.

It’s windy in this season, on that coast, and dry. A bit like parts of Texas as your plane comes down over the mountains to bring you heavy-headed cows and bony horses, looking sun-bleached and moving slow in yellow fields. To soothe winter guests’ disappointment, the resort creates an artificial jungle around the public paths and pools. (Spurning the golf carts for hidden footpaths, we kept getting in the way of the many gardeners.) But the shoreline can’t help but look a little scrubby, windswept, wild. The first day I’d plunged in and been stung by a jellyfish in under 10 minutes. The ocean harbors no tourists—only residents and intruders.

That morning, I’d looked at my weather app and said to my wife, “Hm, looks like it’ll be very windy between 1 and 2, and then calmer the rest of the day.” Then we ate a free $75 breakfast, got massaged, made ourselves alternately too hot and too cold on purpose in the plunge pools.

By that time it was around 1 p.m. and anything I’d thought or said in the morning had melted from my mind. On our group’s agenda, the official activity for this afternoon—our last at the resort—was “leisure time.” Daiquiris delivered poolside, etc. Time to clean our plates of this outrageous feast before being shipped back to a world in which invisible helpers would not sneak into our rooms, plump our pillows, and arrange our sunscreen bottles, discarded socks, and magazines into artful little still lifes twice a day.

“Should we go kayaking?” I said.

We went down to the beach. Flag: yellow. Waves: whitecapped. Kayak attendants: skeptical. They asked if we were experienced. “Yes!” we chirped. (We own a canoe and have kayaked plenty; seemed like that ought to serve.) We signed a waiver. I didn’t catch this at the time, but my wife told me later that they apparently had to inform the local coast guard that a couple of dumb tourists were heading out into the ocean today on purpose.

“Estas chicas tienen mucha experiencia,” one of them said into a radio. Well, hold on, we hadn’t said mucha—but no matter, now it was happening, we’d passed inspection, been given the benefit of the doubt as generously as we’d been given everything here.

“You want to keep your sandals on,” said one of the attendants, her own feet bare, as we headed toward the water. “Me, my feet are tough from this, but the sand is hot.” It was. My wife and I strapped on life vests, pushed off, and aimed our hunks of plastic into the wind.

It was rough going, which was wonderful at first: work to do! Struggle with the elements! In a small boat on choppy water you want to meet the waves head on, break them with your bow. I grinned into the spray that dashed my face. To know what you are doing in a situation of mild difficulty—no better feeling, and no better remedy for the quite opposite feeling of being a tourist at a luxury resort.

On we went, slow as Zeno. The wind stole my hat. At one point the gusts seemed to mass into a wall I could not push through.

“Should we turn around?” I called to my stronger-shouldered wife ahead.

“Why?” she called back, and then the wind let up a bit anyway, so I had no argument for that.

Finally we closed in on the tiny peninsula the staff had asked us not to go beyond, so it was time to turn around and let the wind whisk us back: the easy part, and another part of how I came to be sitting and lightly screaming in the Pacific surf. I tried to turn the kayak, but the wind didn’t want to push me back in the direction we came from. It wanted to run me straight toward the shore. I maneuvered and maneuvered, getting nowhere.

Then I spun sideways, fitting my boat neatly into the palm of a big wave.

I flipped over, went under, came up spitting salt water. One sandal vanished instantly; the other I soon kicked free to keep my focus on swimming to shore and my grip on paddle, boat and dry bag. We were farther out than I’d judged, and encumbered as I was, I wanted to reach land as soon as possible. Every few dog-paddle strokes I stretched my toes toward bottom.

The first thing my feet found was some big white rocks.

The next thing my feet found, according to my feet, was knives.

I thought wow, extremely sharp rocks and called out to my wife, still in her boat, “Watch out, there’s a bunch of rocks!”

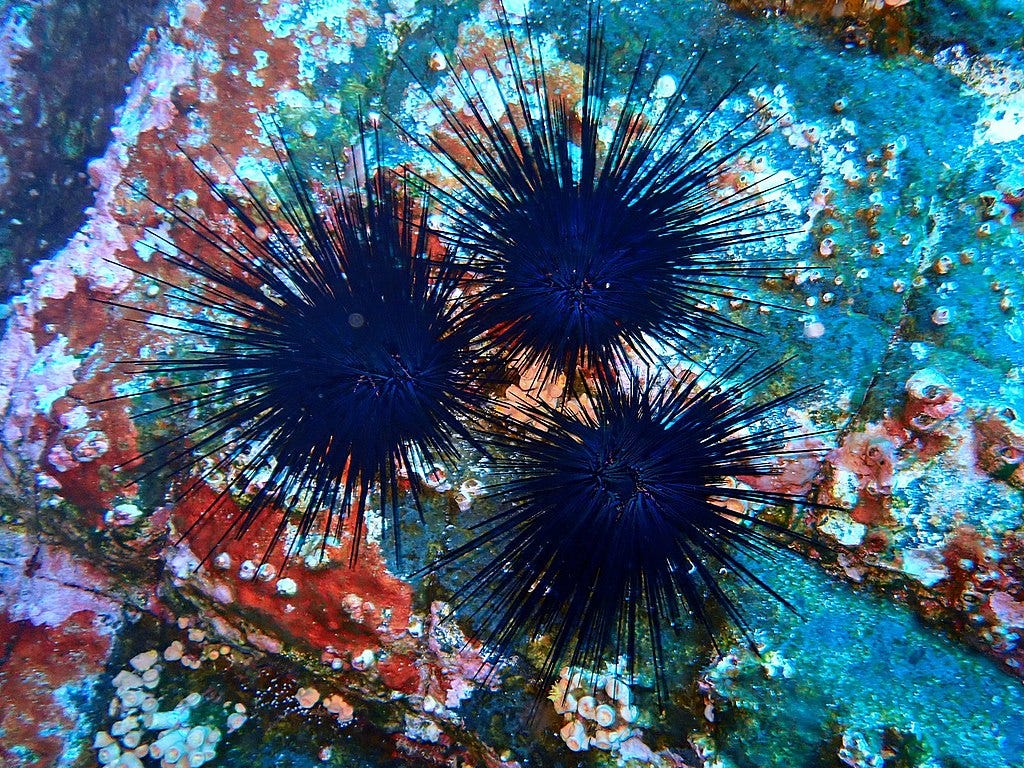

Then the pain in my feet began singing at storm-siren pitch and volume, nerves waking up like all the dogs in the neighborhood joining in. The chorus summoned my attention to a dark patch between the pale rocks. Oh: sea urchin, I thought then, although I’d never seen one in the wild or spent a second of my life supposing that I might encounter one.

I stumbled to the shore and collapsed. My feet—the right one mostly—were tattooed with throbbing purple dots. I pulled out one spine the size of a leatherworking needle, but the others were already broken off under the skin.

“Can you go get help!” I shouted at my wife, who was doing something with the boats.

She went off down the sand. I began experimenting with my series of unsettling noises. I discovered that my feet hurt a little less if I kept them submerged, so I sat there like a shipwreck at the waterline. I squeezed sand in my fists as the waves of pain came and came.

When my wife came back after (according to my feet) a few weeks, she was alone.

“IS SOMEBODY COMING TO HELP!” I squalled.

“Yes, they’re sending someone to come get the boats!”

“THE BOATS?!”

My wife feels terrible about this part. Truly had not understood the state I was in. As for me, I felt exactly like someone stranded on a desert island who’d seen a ship approaching, waved her arms, flashed her signal mirror, made eye contact with the captain, and then watched as that ship sailed past and out of sight.

So that’s when I started laughing a little, too, and chucking rocks into the sea, in between shouting softly in pain and sputtering “The boats?!” and “I thought—I thought you were going to—”

In the midst of my tantrum I remembered we had phones in the dry bag, and my wife managed to reach the trip organizer (“What, this trip didn’t have enough adventure for you?” she exclaimed), and then the army of helpers was activated.

Their first line of defense was fancy bottled water. By the time we made it back to our room we’d accumulated three of these bottles and turned down more. In this phase I still thought someone was coming to provide me medical attention, so I gave an unnecessarily detailed tour of my feet to at least two bemused, non-medical staffers.

Their second line of defense was looking at my feet and saying, “Ah, sea urchin? This has happened to me many times. It hurts a lot?”

I was relieved to hear that my predicament, if terrible, was common. But I did not yet realize that everyone was expecting me to pull myself out of the surf and walk back down the beach after I’d consumed sufficient bottled water. To me, it seemed obvious that someone with so many spikes in her foot should not be walking on that foot. Eventually I communicated this perspective clearly enough that someone was convinced to come get me.

In the meantime it was just me, my wife and one resort staffer left to keep watch. To fill the time, I broke out my Spanish at last. He and I exchanged names and where we lived. We talked about how, yes, I had studied Spanish in school but wanted to learn more and how I was here with my job, which was confusing. I asked for and received the Spanish word for urchin: erizo de mar, the hedgehog of the sea.

A jet-ski pulled up for me, surprisingly. I thought I might have the opportunity to be bucked from two different watercraft in one day. Instead I stayed upright and made it to the main beach, where I was transferred into a balloon-wheeled chair by two more staffers, one holding a pump to re-inflate the wheels as needed.

“Do you want to see the doctor?” someone asked me once I was seated back under a palm tree.

“Yes, I mean, I think I need to get these spines out of my foot?”

“Ah… we’ll see…” came the inauspicious reply.

The doctor, fortunately, was set up in a room right on the beach. She was a bubbly, adorable woman in stylish glasses who plunged my foot into a champagne bucket filled with hot water and vinegar while informing me pleasantly that she was not going to remove the spines because she would have to cut my foot open, because the spines are made of fragile calcium, which breaks into pieces, so you can’t get them all, and no, there was no danger of them moving deeper into my foot, because they’re really very tiny, and some people even go right back to the beach, but you can request white vinegar from room service to soak your foot three times a day, and you should keep looking at it to see if it gets infected, but she had seen many cases and only one had ever gotten infected. After 20 minutes of soaking and chatting, I was released on my own recognizance, my own two thin-skinned feet.

If you search the internet for what to do when you step on a sea urchin, you will find some version of this advice. You will also find “cut them out yourself with a box cutter,” and “get drunk and hit the area with a mallet so they break up and dissolve faster” and “have them medically removed ASAP or you could lose a foot.” I followed the resort doctor’s advice for the time being. I pickled my foot at regular intervals. I limped through the banquet that evening, then through two airports and over a snowbank to my front door the next day.

The pain and swelling did abate. So did the purple dots caused by pigment in the spines’ toxic sheaths—the cause of such outsize pain, I learned upon research. But one spot in particular had a pencil-lead-size spine wedged far under the skin, and that one continued to produce a sickening jolt when disturbed. After a week or so, I went to a podiatrist and had him do as the resort doctor had feared: cut open my foot, to uncertain effect. “The thing is, there’s blood now, so it’s hard to see,” the podiatrist narrated thoughtfully as he worked to dislodge what he could. “I’ve never done one of these before!” he exclaimed afterward.

I’m glad we both could learn something. I still don’t know if it was the right choice, but it was the choice I was bound to make. Becalmed by luxury or calamity, I will always reach for the illusion of forward motion.

Image of diadema mexicanum: Sylvain Le Bris, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons